Obesity Impairs Bone Health in Growing Children

Obesity and type 2 diabetes in teen years can compromise bone health.

In the complex, interconnected machinery of the human body, obesity is like a metabolic domino that can lead to a cascade of health problems. It is associated with an increased burden of cardiovascular diseases, type 2 diabetes, cancers, and infections, among other detrimental conditions.1 Excessive weight and insulin resistance can also overload the musculoskeletal system, ramping up the chances of bone fractures.2 Contrary to these findings, scientists have long considered obesity in childhood to be osteoprotective, stimulating bone growth and slowing down bone loss and damage. Yet, studies investigating the effects of obesity and its comorbidities on bone health in children are sparse.

In the past three decades, the global rate of obesity in children has risen by 12 percent, in part due to poor diet, lack of physical activity, and genetic predisposition. The effects of obesity on the body in childhood can have long-lasting consequences into adulthood.3 Fida bachaa pediatric endocrinologist at the Baylor College of Medicine, studies the complications of this chronic disorder in children. In preliminary findings presented at the 2025 Endocrine Society conference in July, Bacha and her team reported that obesity in teen years can impair bone health, putting such individuals at higher risk of fractures and osteoporosis later in life.

“The older belief was that obesity puts mechanical load on the bones that makes them stronger,” Bacha said. “While the mechanical load is important, there are other factors related to obesity that may cause adverse effects on bone quality and strength”

Bacha and her team previously reported that insulin resistance mediates the relationship between fat mass and bone mass in children.4 Considering the strong link between obesity and type 2 diabetes, the researchers analyzed the effects of both conditions on bone health. The researchers followed 48 teenagers, comprised of three groups: normal weight, overweight with normal sugar levels, or overweight with impaired sugar levels. Of the last group, four had prediabetes and 16 had diabetes. The team measured the children’s body fat, fitness, blood sugar, and insulin levels. They used high-resolution quantitative imaging to examine the structure and strength of the tibia (lower leg bone) and the radius (forearm bone) and observed that bone strength and quality improved the least in the teens with obesity and type 2 diabetes, as compared to those with normal weight. Though the study was done in Houston, Bacha believes that the results are generalizable to children around the world.

“It is important to increase awareness about the effects of obesity and type 2 diabetes on bone development in childhood,” Bacha said. “There’s rapid bone accrual during childhood, which can affect bone strength in later years.”

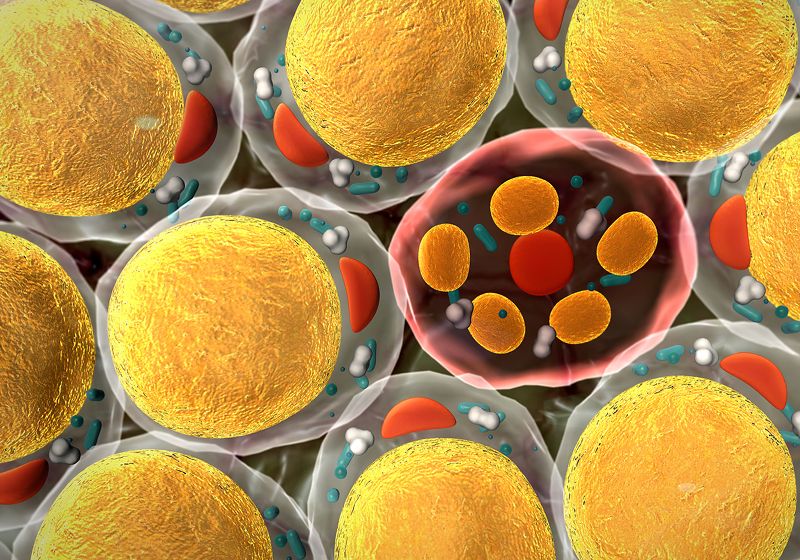

Scientists have previously shown that obesity can stimulate bone marrow stem cells to differentiate into adipocytes, at the expense of bone cell formation, in rats.5 This results in bones that have high mass due to fat deposition but are weaker than normal. Bacha’s findings strengthen these reports and warrant further investigations. Next, she intends to investigate the mechanism that drives the decline of bone health in children with obesity and type 2 diabetes. “Once we understand the underlying pathophysiology, we can intervene to prevent bone deterioration,” she said.