Sustainable Practices Utilizing Genomics in New Zealand Wine Production New

Estimated reading time: 8 minutes

New Zealand’s wine industry stands as a critical contributor to the nation’s economy and reputation on the global stage. However, climate variability, disease outbreaks, and growing environmental concerns have placed pressure on vineyards to adopt more sustainable practices. By embracing cutting-edge genomics, New Zealand wine producers are revolutionizing the way they approach crop breeding and pest management.

The Value of New Zealand’s Wineries

New Zealand’s wines are gaining popularity for their quality and unique flavors, leading to strong demand in international markets.

istock, Edsel Querini

A Thriving Economic Contributor

New Zealand’s wine sector has grown into a key economic pillar, exporting to over 100 countries and generating billions in revenue annually. According to viticulturists, wine ranks as the seventh-largest export in New Zealand’s economy, with the top markets being Australia, the United States, the United Kingdom, and Canada. The consistent growth in export volume reflects both the international appeal of New Zealand wine and the industry’s resilience and innovation.

Unique Terroir and Varietals

New Zealand is celebrated for its distinctive wine flavors, particularly its Sauvignon Blanc, which thrives in the country’s cool climate and varied terroirs.1 Each region, from Marlborough to Central Otago, offers unique soil and climate conditions that influence grape character. This diversity not only caters to a wide range of wine consumers but also adds depth to New Zealand’s viticultural heritage.

Employment and Regional Development

Beyond exports, the wine industry supports local economies by providing employment and stimulating tourism.2 Vineyard development has led to infrastructure growth in rural areas, helping communities flourish. Seasonal work during harvests and bottling seasons also supports labor markets, and the industry’s commitment to sustainability enhances its appeal to eco-conscious travelers and investors.

Sustainability in Wine Production

In recent years, sustainability has become a key focus in New Zealand wine production.

istock, Firn

A Growing Need to Defend Native Biomes

New Zealand’s vineyards are seeing the effects of climate changefrom irregular rainfall to uncharacteristic temperature ranges.3 These changes can make grapes more susceptible to mildew, rot, and stress, directly affecting yield and quality. Facing increasing climate pressures and public concern over chemical useNew Zealand wine producers are pivoting toward environmentally friendly growing techniques.4 Organic and biodynamic farming practices are on the rise, with vineyards minimizing synthetic inputs and adopting natural pest deterrents.4,5 This aligns with New Zealand’s clean and green brandingand many vineyards are now certified sustainable or organic.1,6

Shifting Toward Organic and Biodynamic Practices

Viticulturists and plant researchers are particularly concerned about long-term soil degradation and the impact of pesticides on native biomes. “We have a number of the common diseases and pest species which affect production. We rely very, very heavily on chemical application of fungicides, in particular, to control powdery and downy mildew and Botrytis,” explained Christopher Winefieldplant molecular biologist and geneticist at Lincoln University, whose research focuses on crop evolution and genetic strategies to improve horticultural plant species such as grapevine and hops.

The traditional use of fungicides, herbicides, and insecticides, while effective in the short term, can compromise soil health and lead to chemical resistance in pests.2 Farmers are increasingly looking for pest management strategies that reduce the need for chemical application to maintain vineyard health. “I think some of the biggest challenges that we face in the viticulture and wine industry is actually precision. I can see further and further that the wine consumers of the world will be wanting to know exactly what and how we’re spraying,” said Timbo Deaker, a viticulturist from Viticultura, in a recent interview.

Improving Biological Resilience

Sustainability is not only about reducing what goes into the ecosystem but also building resilience within the system. Farmers increasingly turn to strategies that protect the soil, such as cover cropping (i.e., sowing other plants into the vineyard below the grape vines), mulching, and improving water management to stabilize vineyard ecosystems.4 Scientific solutions that learn from and build upon a crop’s natural resistance are new approaches that provide growers with hope that they may one day rely less on chemicals.7 “We’re very excited by some new genetics coming out about vines that won’t require spraying. The idea of becoming a lazy grape grower has great appeal to me,” said Deaker.

Breeding Better Adapted Plants

Scientists use genomics to breed plants that are better adapted to resisting pests and diseases.

istock, Casarsaguru

Harnessing the Power of Genomics

Winefield and his research team are pioneering the use of genomics to create grape and hop varieties that can naturally resist disease and adapt to changing climates. By decoding the genetic makeup of different plant strains, the scientists work to identify key genetic traits responsible for resistance and vigor, eliminating much of the guesswork from traditional breeding.

“Our role here is to look at ways of not only genetic improvement through stimulating our vines to generate new genetic variants, but also to use biotechnological approaches that are not genetically modified,” explained Winefield. “The technology which really starts to help us in this space is genomics, to breed plants that are better adapted to resisting these diseases.”

Replacing Chemical Dependence with Natural Resistance

Winefield aims to reduce dependence on pesticides by breeding plants with natural resistance to pests such as mildew, phylloxera, Botrytisand other common vineyard detriments that can devastate crops and often require costly interventions.

“We and others across the world have identified a number of particular targets, which, if altered in terms of how they behave within the grape plant itself, can lead to resistance, for example, to powdery mildew,” said Winefield. “We have, with Bragato (Research Institute), produced a number of Pinot Noir genomes and Sauvignon Blanc genomes that we’re now starting to interrogate to understand how these clones differ and whether we have an ability within those clones to identify differences which will lead to production, eventually, of a more tolerant vine.”

By selecting genetic variants that show natural resistance, researchers hope to create plant lines that can thrive with minimal synthetic support. This not only preserves the surrounding ecosystems but also reduces the carbon footprint associated with chemical manufacturing and application.

Expanding to Hops and Beyond

While wine grapes are a key focus, the same genomic principles are being applied to other crops, including hops, which are vital to New Zealand’s booming craft beer industry. Similar to grapes, hops suffer from fungal and pest pressures that genomics can help counter. “We know chemicals are not very nice to plants, and in the long term, definitely looking into genomics and making varieties resistant is probably the right way to go,” said Blaz Jelen, a hop production manager from Garston Hops. This holistic view of agricultural sustainability points toward a future where New Zealand can lead globally in science-backed farming methods without relying on chemical pesticides.

Leveraging Genomics Technology for Wine Production

The cost-effectiveness and Q40 quality of MGI sequencing supports researchers investigating plant breeding, enabling larger-scale studies that enhance grape and hop yield.

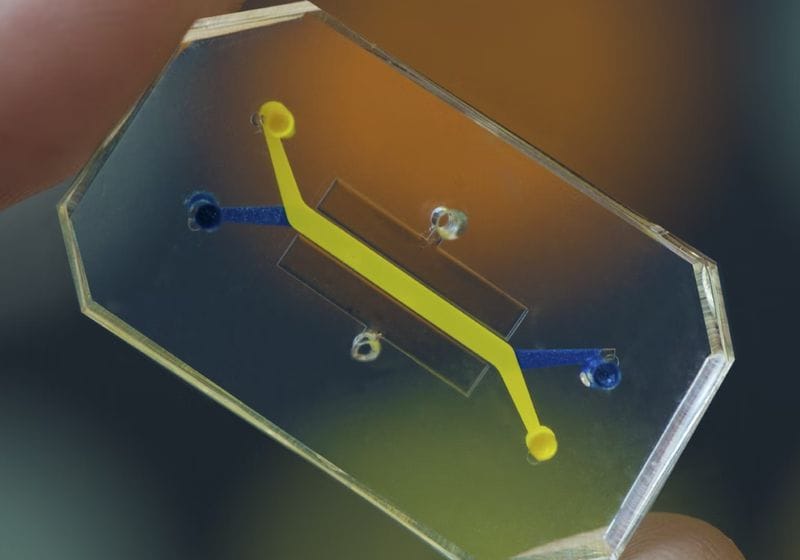

istock, Geobacillus

Adoption of MGI Sequencing Technology

To accelerate genomic research, Winefield adopted MGI sequencing technology in his laboratory. This next-generation tool is known for its cost-effectiveness and high-quality data, enabling Winefield’s team to analyze thousands of grape and hop samples at scale, identifying genetic markers with unprecedented precision.

“Previously, we’d been using international sequencing providers to take our samples and do the sequencing and deliver that data back to us. Those options are not that cost-effective,” explained Winefield. “The opportunity came two or three years ago to trial the MGI DNBSEQ G400. The introduction of MGI sequencing tools has really helped democratize sequencing for small teams like myself.”

From Genomic Data to Field Success

The introduction of MGI’s platform has democratized access to genomic data, allowing for deeper and broader studies without prohibitive costs. It is a game-changer for plant breeding, offering a viable path forward for both research institutions and commercial growers.

“The cost of that sequencing is highly competitive, in particular with the new release of the Q40 chemistry,” said Winefield. “At the moment, we can process maybe 200 samples in a fortnight. We’re looking in the near future to move that to 50,000 samples a year. We can’t do that without MGI’s support.”

With MGI-generated Q40-quality sequencingresearchers are now able to build comprehensive genetic maps of plants, linking genes with traits such as flavor profile, pest resistance, and drought tolerance. These insights inform breeding programs that are already producing promising new cultivars. Such precision breeding ensures that new varieties are not only more sustainable but also retain the high quality for which New Zealand wines are known.

A Blueprint for the Future

Through the strategic use of genomics, researchers and viticulturists are solving immediate challenges and paving the way for a more resilient agricultural system. From protecting soil environments to preserving crop health, integrating genomics into wine production offers a replicable, scalable path toward true sustainability.

The path forward is rooted in science and sustainability, with high-quality sequencing technologies helping scientists and farmers breed disease-resistant grapes and reduce pesticide use. As climate threats grow and consumer preferences shift toward eco-friendly products, New Zealand’s commitment to sustainable genomics-based viticulture places it at the forefront of the global wine industry.